Unpathed Waters, Undreamed Shores[1]

Watery Tales from Llyn Tegid

Llyn Tegid, painted by Alphonse Dousseau in the mid 19th century

There are so many stories about Llyn Tegid, Bala Lake, the surrounding landscape and rivers. Let’s start with a tale of how the lake came to exist:

Long ago, the legendary Tegid Foel, husband of Ceridwen and chieftain of Penllyn, also ruled a fine city where now stands Llyn Tegid. In his pride, it’s said, Tegid invited many important people to a celebration and hired the greatest harpist in Wales to entertain the guests. All was going well until a small bird distracted the musician with its beautiful song, so that the enchanted harpist followed the bird up onto the hillside overlooking the city where, tired from his exertions and lulled by the bird’s song, not to mention the ever-flowing wine, the musician dozed off, only to wake with a start at first light. How the landscape had changed! The city was no longer in sight and a lake, upon which floated a harp, now filled the valley.

To this day, some people say that the lights of the old city are occasionally glimpsed below the water and fishermen claim to have seen chimney pots around Llangower Point, not to mention the bells that are sometimes heard. Another version of the tale has it that the harpist was tasked with replacing the stone “Llech Cywair” on Gwawr’s holy spring, but forgot, so that it overflowed, with precisely the same result – Llyn Tegid!

Llangower is a truly magical village on the lakeside. Afon Gwawr flows by its tiny church and, close by in the churchyard, ancient graves cluster round a yew tree which has seen at least a thousand years come and go. As the church is no longer in use people rarely visit and the churchyard is sprinkled with a huge variety of wildflowers at this summer solstice time.

Church of St Cywair (or Gwawr), Llangower

Ffynnon Gwawr, or Gwawr’s Spring, did indeed lie close to the church but is now, alas, nowhere to be seen. Ann Roberts, who lives locally, told me recently that the well had been thought to cure rickets, but believes it now lies somewhere under the B4403 road between Bala and Llanuwchllyn.

But long before Ceridwen’s days of gathering around Llyn Tegid, another story tells of how she came to live here with Tegid Foel. He had gone sea fishing in his boat as a young man, but was somehow driven to an area where the sea was like glass and very bright, and below he could see fields, groves, hills and rivers, and even people dancing to music that he could hear from below the waves. Local fishermen had told Tegid there was a dangerous sea serpent in this area, and suggested he destroy it, but when he approached a deep voice warned the young man “Do not kill your sister.”[2]

That night Tegid returned and called out to his sister, who approached him while still in her serpent body, but Tegid is then attacked in very strange and elemental ways, first an ocean he must cross, then a cliff of ice to surmount, now a white-hot furnace. Was this a test such as the one a shapeshifting Gwion Bach survives after appropriating the three drops of Awen meant for Morfran?

Tegid, of course, survives and settles permanently on his father’s grave mound, where Ceridwen also decides to make her home, following which, as the folk tale puts it, “the two were joined”.

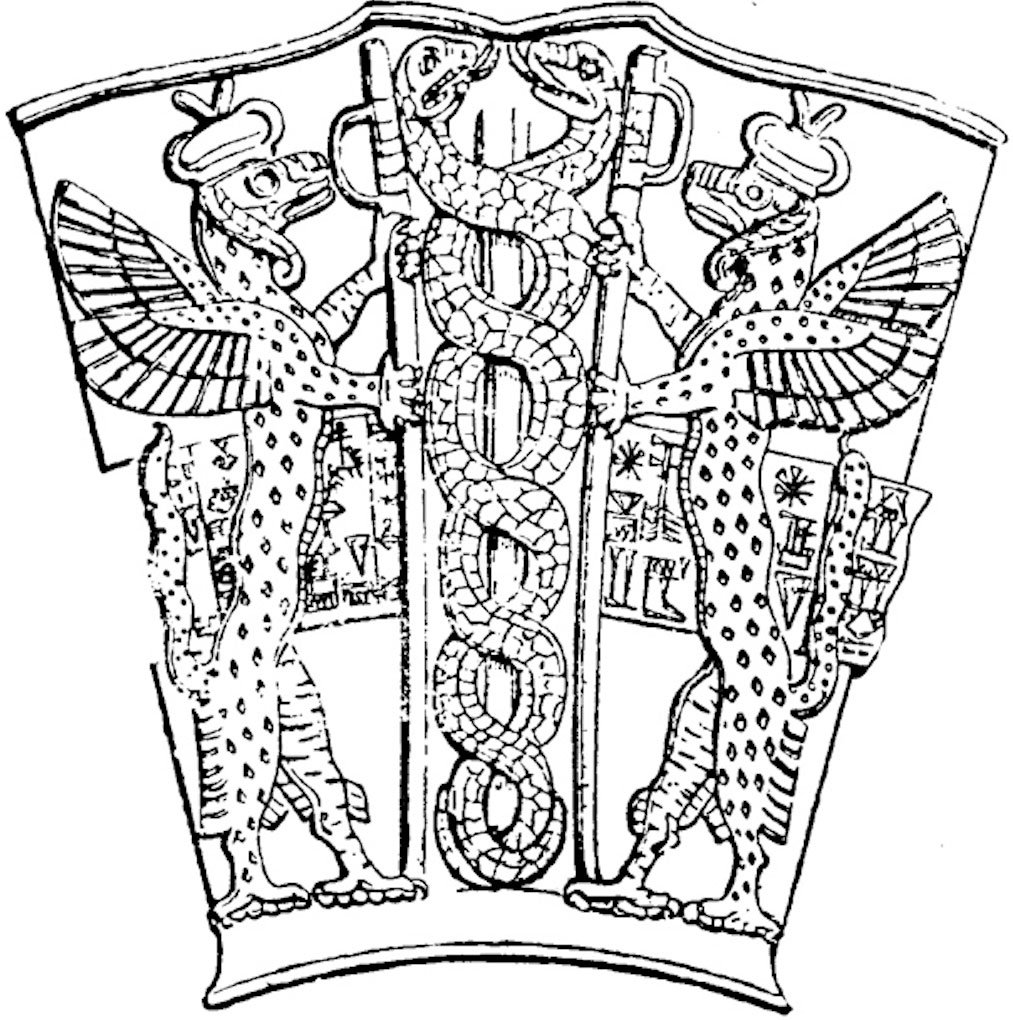

Still today the pair appear as intertwined serpents from time to time, echoing some of the world’s oldest mythology: for example Mesopotamian goddess of healing and magic Ningizzida had twined serpents as a symbol (Ningizzida is reported by some to be a god, but the word Nin probably meant “Lady” in the Akkadian language). Myths involving snakes, staffs and trees are so common as to be found all over the world and it’s interesting that both Ceridwen and Ningizzida are deities of healing and magic…. not to mention Brigid, also very much associated with healing, and it is worth remembering that the caduceus, a staff entwined by serpents, remains a symbol of healing to this day.

This story of Ceridwen and Tegid and the connection with salt and fresh water brings to mind another Mesopotamian story, that of Tiamat and the bitter and sweet waters.

Ningizzida, thought to be represented by the central staff and serpents

Tiamat is depicted in many tales as a serpent or dragon, and personified the salt sea, or bitter waters. The sweet water of lakes and rivers is embodied by the god Abu and, according to the Enuma Elish, Tiamat and Abu mingle their waters together to create the gods. One of this new generation, Marduk, kills Tiamat[3] and from her body creates heaven and earth, from her eyes the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, while from her breasts mountains were formed.[4]

The name Mesopotamia means “between rivers” and this connection becomes all the more fascinating on discovering another story, this time of the two springs from which Llyn Tegid was formed, known as Dwyfan and Dwyfach. The rivers which these springs developed into were said to flow through Bala Lake but without mingling with its water. Both names Dwyfan and Dwyfach are related to that of the sacred River Dee, whose correct name is Dyfrdwy – the waters of the divinity.

There’s also an old story about salmon coming to shore on the banks of Dwyfan and Dwyfach on Christmas morning, and helpfully allowing themselves to be tickled like trout and lifted out of the water. Perhaps this originally took place at the Winter Solstice but moved to Christmas with the new religion? In any case, when the Gregorian calendar came into use in 1753 and 11 days were dropped to bring Britain into line with most of Western Europe it didn’t go down very well, there were demonstrations and even riots. Perhaps the salmon were also offended by the change, as they never again offered themselves up in this way.[5]

Even more obscurely, I found a reference to an ancient name for the Dee as Danuvia, but this intriguing connection will have to wait for another time!

Just as serpent symbolism appears ubiquitous, so too are stories of a world-destroying deluge, so perhaps not so surprising to read that a personified Dwyfan and Dwyfach also have a part to play – the couple escaped the great flood in a mastless ship named Nefyddnaf-Neifion, which bore a pair of all living creatures. Once the floodwaters receded, they repopulated the isle of Prydain, now called Britain.[6] Sound familiar? Sadly, Dwyfan and Dwyfach are nowhere to be found today, although there is an Afon Dwyfor that meets the sea near Criccieth.

Bala Lake has flooded the town in the past, but embankments and other protections have been put in place over the years and more work is expected to begin soon. But could the town flood again? Perhaps this folk rhyme will provide the answer:

“Bala old the lake has had, and Bala new

The lake will have, and Llanfor too.”

Geraldine Charles

22 June 2021

[2] Rhys, John “Welsh Fairy Tales”, Y Cymmrodor, Vol 4 (1881)

[3] Robert Graves (in The White Goddess) saw the Enuma Elish as a response to the loss in status of the goddess and the poem as an artistic representation of the rise of the patriarchy.

[4] Sacred-texts.com. 2021. ENUMA ELISH. [online] Available at: <https://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/enuma.htm> [Accessed 22 June 2021].

[5] Jones, Francis, “The Holy Wells of Wales”, University of Wales Press (1992)

[6] Sacred-texts.com. 2021. Celtic Folklore, Welsh and Manx, by John Rhys index. [online] Available at: <https://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/cfwm/index.htm> [Accessed 22 June 2021].