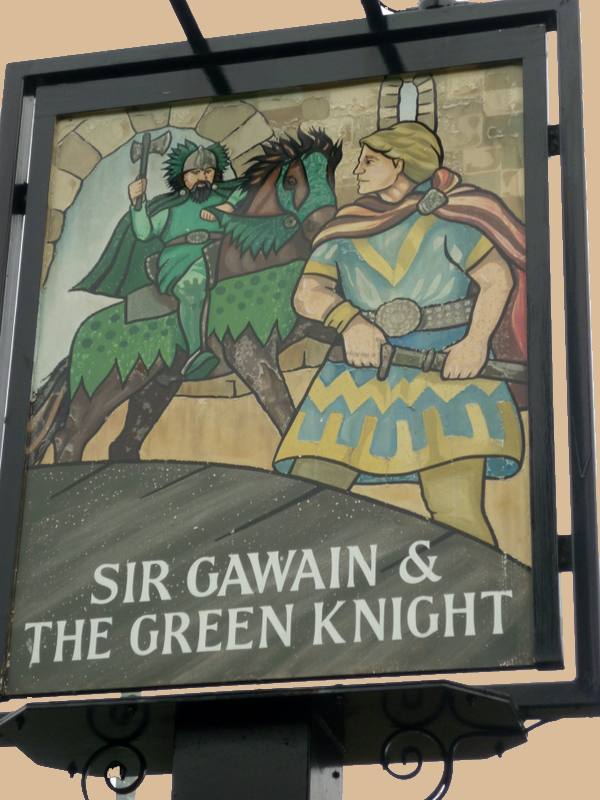

The Goddess, Sir Gawain, and the Green Knight – Yule 2021

Pub Sign from Connah’s Quay*

“Morgan the Goddess” is probably the last person I’d expect to meet in a late 14th century English poem, even if that composition were set in a mythic past—after all, Christianity had been well established in Britain for centuries by this time and that’s certainly demonstrated in the rest of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Alliterative poetry of the type we find in the much earlier Beowulf had become fashionable again and perhaps harking back to the glorious days of Arthur’s reign was a comfort after a truly appalling century, abounding in plague, war, poor government and famine.1

Let’s start with a summary of the poem’s story:

King Arthur, his court and the knights of the Round Table were tucking into their Christmas feast at Camelot when a mysterious knight with green hair and skin, riding a green horse and holding a sprig of holly, arrives and challenges the stunned revellers to a game: the person who accepts his challenge may strike the knight with his own axe, on condition that the antagonist finds him in exactly one year to receive a blow in return.

Arthur hesitates but steps forward after being mocked by the knight, however Gawain quickly takes the axe and cuts off the knight’s head with one blow. But to the astonishment of the court the knight picks up his severed head, reminds Gawain of the terms, and rides away.

When the following Christmas is near, Gawain puts on his best armour and rides off through North Wales towards the Green Chapel, where he is to meet the Green Knight. Finally, after several adventures, he comes upon a castle, where he finds a warm welcome. His host, Bertilak, introduces Gawain to his lady and to an old woman who sits besides her. He also strikes a deal with Gawain: Bertilak will go hunting every day and on his return will exchange his winnings with anything Gawain has acquired by staying in the castle.

Gawain sleeps late the next morning and wakes to find that Bertilak’s lady has sneaked into his chamber in order to seduce him, although she succeeds only in stealing one kiss, which Gawain duly passes on to Bertilak on his return from the hunt. On the second morning there are two kisses from the lady, while on the third she gives Gawain not only three kisses but also her green silk girdle, which has the magical ability to protect its wearer from death. Although all the kisses are passed on to Bertilak as agreed, Gawain doesn’t mention or pass on the green girdle.

The fourth morning brings Gawain’s promised meeting with the Green Knight, and he rides forth in his armour and wearing the green girdle. As promised, he presents his neck to the knight but receives only two feinted blows and a final one which merely nicks the skin. Only then does the Knight reveal that he is in fact Bertilak and has only scratched Gawain’s neck because the latter was not honest about the green girdle. He also tells Gawain that the old woman in his castle is actually Morgan le Fay, who was behind the plan to change Bertilak’s appearance and send him to Camelot.

You’d be forgiven for believing that the motive behind Morgan’s plan was indeed wicked, given the set of theories we’re presented with by many writers. In The Idea of the Green Knight, Besserman2 tells us that Morgan sent Bertilak to Camelot in the alarming guise of the Green Knight in order to frighten everyone out of their wits and Guinevere to death. If that is true, Morgan the Goddess failed. Guinevere is unharmed and the rest of the court seems to recover well enough. But can this really have been Morgan’s intention? After all, as the poem makes clear, Morgan

“… by cunning and practice and by crafts well-learned,

And the magic of Merlin, much of which she has knowledge….

…There is none of great highness

who she cannot make tame.”3

It’s worth bearing in mind that most people at the time believed absolutely in magic, a state of affairs that continued for centuries into the era of the Witch Trials and beyond.

Around the late 14th century storytellers had begin to examine the fall of the Round Table, Emily Dangerfield4 tells us, and perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised to find that the fault was now being laid at the door of women, supposedly dangerous because they were incapable of a proper understanding of chivalric values, and all the more because of their seductive power over men.

In “The Role of Morgan le Fay in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight”, Baughan5 writes that it would be hard to find a character so misunderstood and neglected than that of Morgan. As I noted above, the consistent picture we’re given has been of the failure of Morgan’s plan. Baughan believes that on the contrary, Morgan did not fail; the beheading game was not a physical test for Arthur but a device to lure Gawain to Bertilak’s castle. Remembering that Gawain features as hero in many English works, including possibly as the original hero of the Holy Grail story, we’re already aware of Gawain’s courage and faithfulness to Arthur. The real test faced by Gawain, however, required no physical courage, but the virtue to withstand seduction by Bertilak’s lady, through which Morgan perhaps hoped to compare her nephew Gawain’s temperance and chastity to the moral ambiguities of Camelot, portrayed in many other romances of the time. “… it is inconceivable”, writes Baughan, “that the poet should have viewed her as a cheap enchantress.” Her fame as a healer suggests that Morgan sending Bertilak to court was intended “to purge and heal the court of its moral corruptness.”

Bearing in mind how such Christian virtues as chastity were seen at the time the poem was written, and perhaps especially so given the times people were living through, we can agree with Baughan that Morgan was in fact carrying out the sacred healing work of goddess, just as she was there to help and heal Arthur after his final battle.

Loomis6 takes this view further and believes that many of the elements of this poem and other works about Gawain are also present in Mabonogi tales, with echoes in more recent Welsh folklore and custom, and furthermore that Morgan (called “Morgne” in the original Middle English of the poem) was identical with Modron. “It was a long and a strong tradition”, adds Loomis, “which brought Morgne into GGK.”

There is so much more in Gawain and the Green Knight that’s intriguing; I have a long list of questions still to address, including the location of the Green Chapel and the reason why the Knight is green. We’re also told that Gawain carries a “pentangle” on his shield and I will confess that I wasn’t entirely sure what that meant – in fact it’s a synonym for “pentagram” so immediately that, together with the green garter that Gawain was gifted, also become subjects for future research! An expanded version of this and other blog posts together with new articles should appear in my forthcoming book.

In the meantime, perhaps we should be looking out less for King Arthur returning in our time of need and more for Morgan, who bears just one of the many names of our Once and Future Goddess.7

Geraldine Charles

December 2021

- Tuchman, B W (1979) A Distant Mirror: the Calamitous 14th Century, Penguin

- Besserman, L. (1986). The Idea of the Green Knight. ELH, 53(2), 219–239

- Smith, Michael, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Unbound, 2018, 139

- Emily Dangerfield: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and the Threat of Women to Courtly Life, available https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10214/4026/Emily_Dangerfield_0638289_Atrium.docx?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Baughan, D E, “The Role of Morgan le Fay in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight”, ELH, 17(4), 1950

- Loomis, R. S. (1943). More Celtic Elements in “Gawain and the Green Knight.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 42(2), 149–184 1943

- It would be quite wrong of me to steal this quote from the title of Elinor Gadon’s excellent 1989 book of the same name without giving some details in full: Gadon, E (1989) The Once and Future Goddess: A Symbol for Our Times, Harper Collins

*Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Ian S – geograph.org.uk/p/2722176

** Lud’s Church image by August Schwerdfeger, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons