Skeleton Trees and Swan Maidens

What could be sadder and spookier at Samhain than the 18th century tale of Meinir and Rhys, childhood playmates who grew up to find true love together? They lived at Nant Gwrtheyrn, a tiny place near Llithfaen on Llŷn, and planned to marry at St Beuno’s church in Clynnog-Fawr, a few miles away. Perhaps they plighted their troth at their favourite spot, an oak tree on Yr Eifl, one of the highest hills on the Lleyn peninsula.

Llyn y Fan Fach from Waun Lefrith1

There was a tradition in the Nant known as “The Wedding Quest”: the bride was to run and hide on the morning of her wedding, so while guests assembled at the church Meinir took to the hills and Rhys’s friends searched for her. But they could find no trace of the young woman. Eventually Rhys left the church and joined the search, which continued far into the night by torchlight, but eventually he was left alone to seek his bride. And he continued to do so for some thirty years, slowly losing his mind in the process. Then one day he took shelter from a storm under their beloved oak tree, when suddenly a huge lightning bolt split the tree in two. Rhys couldn’t believe his eyes – there inside the tree was a skeleton in a wedding dress. Overcome, he collapsed and died on the spot, holding his beloved in his arms.

To this day, it’s said, a couple is sometimes seen on the beach there, the man bearded and the hollow-eyed woman in white, and that only owls and cormorants will land on the hollow tree; other birds avoid it.

Nant Gwrtheyrn seems to have suffered more than its share of unlucky incidents over the years, perhaps begun by three monks on pilgrimage from Clynnog to Ynys Enlli (Bardsey Island) at the beginning of the 6th century CE, who happened on the valley and decided to build a church there. Locals had other ideas, however, and threw stones at them, forcing the monks to retreat. As these early Christians so often did, the monks set curses on the local community: first that the valley’s ground would never be holy and no-one would ever be buried in its soil; second that the valley’s community would succeeed then fail no less than three times, with the third fail permanent. Thirdly, that no members of the same family would ever be able to marry one another. No time was wasted: on the very evening the monks departed all the local fishermen, which meant virtually every man in the Nant, drowned in a storm, forcing their womenfolk to leave. Thus the

Nant settlement fell for the first time. But it is entirely possible that the Roman Church put this story about as propaganda, as they were attempting to bring the Celtic Church under the banner of Rome.

Chwarel Porth y Nant, Nant Gwrtheyrn2

There were perhaps only three farms in the whole of Nant Gwrtheyrn in Meinir’s time, and so it’s likely that, as some say, Rhys and Meinir were cousins and so the monks’ curse was perhaps responsible for the tragedy.

Today there is a Heritage and Welsh Language Centre in the Nant, and a symbolic tree commemorates Meinir’s story. But the curse remains; could the Heritage Centre be lost due to this?

This is a popular story in Wales and indeed isn’t the only Skeleton Tree legend, there’s also a well-known one from around Dolgellau.3 Another popular tale is that of the Lady of the Lake, as the woman who emerged from Llyn y Fan Fach in Carmarthenshire is known. A young man who was grazing his cattle and sheep around the lake was dreamily gazing into the crystal-clear waters when he was astonished to see a beautiful young woman slowly walk out of the lake towards him. He fell in love on the spot, caring litte if she were fairy or goddess. She told him that if they married a prosperous future awaited them and he agreed immediately, despite the conditions the lady set – that he must never strike her three times, and also that he must never tell anyone where she had come from.

And over the years the couple did indeed become prosperous, with three fine sons born to them.

The first blow was almost playful, just a flick, but it counted. On another occasion they attended a christening together and he struck her because she wept at this happy occasion, although she explained that her second sight told her that the babe would suffer and die young – and indeed, soon they were attending that poor child’s funeral. Once again, the lady was thought to have behaved inappropriately because she laughed out loud. Despite her explanation that now she saw the baby happy and well in the Otherworld, her husband struck her for the third time whereupon she declared their marriage over and walked back to the lake, taking with her all the otherworldly animals that had formed her dowry and leaving her husband and sons weeping on the lakeshore.

It’s said that the lady occasionally appeared to her sons when they visited the lake and taught them the arts of medicine and herbalism, thus they became the great healers we know today as the Physicians of Myddfai.4

At first sight these stories aren’t very similar, except for the missing brides. The Llyn y Fan Fach tale is like many others found throughout the world and the women in these stories are known to foklore enthusiasts generically as Swan Maidens, probably because in many of the tales the man takes possession of the maiden’s skin of feathers while she is bathing, thus preventing her from flying away and forcing her to wed him. Of course they are not always swans but creatures found locally, so that in Scotland and Scandinavia the maidens are often Selkies or seal maidens, whose seal skins are taken and hidden in the same way. But the idea of the reluctant bride, the captured woman, does indeed link these tales.

Even in the Rig Veda, some of which dates back in oral transmission some 5,000 years, there is the story of Urvasi, an apsara or semi-divine being, and the mortal King Puravas, who saw the apsaras taking a bath in the forest and immediately fell in love with Urvasi. She agreed to wed him, with conditions, but as in the Lady of the Lake story these are broken and she returns to her home.

As part of this story Urvasi compares herself to the wind: “hard to catch and hold”. 5 This momentarily took my breath away, for shortly after my mother’s death my father spoke of her in very similar terms. “I could never catch her…”, he said sadly. It made immediate sense to me; she had been quicksilver to his lead.

There are cultures in which marriage by capture still takes place but this has been practiced across the world at various times and no doubt it was sometimes just a way for a couple to get round local customs that wouldn’t allow them to marry otherwise. But sadly, marriage by capture—and worse—is still only too common in war zones.

Perhaps Meinir’s tragic disappearance was a dim memory of when brides were captured, although it is certainly possible that churchmen obsessed with female virginity imbued young women with so much shame that the older tradition became twisted, that she ran to indicate her maidenly reluctance to be initiated into sexuality.

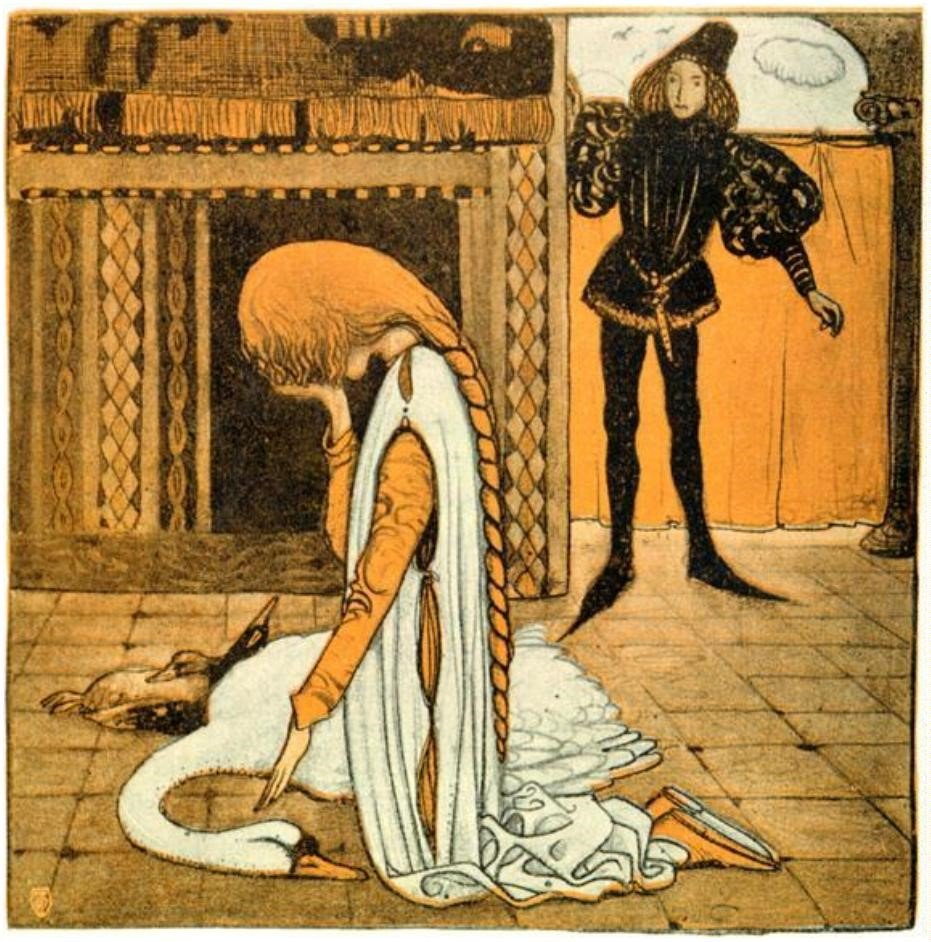

Swan princess crying, by John Bauer

These tales are so full of ambiguities! Perhaps necessarily so for the relief of stress caused by the impossibility of fitting everyone into the dualistic boxes that seem such an important part of patriarchy. So often in the stories the swan maidens become subservient, even domestic drudges, but retain the hidden ability to retrieve their skins and remove themselves from the situation if it becomes unbearable, a remedy far less available to many women even in today’s world. Capturing a woman to wed may mark the triumph of culture over nature, with man representing culture while woman is seen as nature, as only too ready to return to the wild.6 This is certainly an oversimplification of the differing and complex ideologies and social structures surrounding the place of women in the world, but the fact remains that the universality of this symbolism, despite variations, remains. Not for nothing are Swan Maidens “hard to catch and hold”, for in the end they are, after all, Everywoman.

Geraldine Charles

October 2023

- Bibeyjj, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Llywelyn2000, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Dean, R. (2017) Folkore of wales: The skeleton tree, Derwen Ceubren yr Ellyll, FolkloreThursday. Available at:

https://folklorethursday.com/folktales/folkore-wales-skeleton-tree-derwen-ceubren-yr-ellyll/ (Accessed: 15 October

023). - You can read more about this here: https://myddfai.com/meddygon-myddfai-physicians-myddfai/

- Leavy, B.F. (1995) In Search of the Swan Maiden. NYU Press.

- Ortner, Sherry B. 1974. Is female to male as nature is to culture? In M. Z. Rosaldo and L. Lamphere (eds), “Woman, culture, and society”. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press