Mari Lwyd – a Horse at Midwinter

The storm is coming, by Natalie DeCorsair1

If you live in south Wales, especially Glamorgan or Monmouthshire, a strange procession might appear at your door sometime around Christmas or New Year. A leader, perhaps smartly dressed, with a motley crew of people, two of them dressed as Punch and Judy, the latter wielding a broom or rolling pin. Sometimes there would be a merryman, who would play music. Most remarkably of all, the chief character is the white skull of a horse mounted on a pole and carried by someone concealed by a sheet. Usually there are ribbons or some kind of decoration added to the skull and sometimes springs fitted to the jaw to facilitate a clacking sound.

After knocking, the company would begin to sing or speak in verse, asking for entry. You’re expected to reply in kind, refusing to let them in. They would persist and once you have run out of excuses or failed to make up more lyrics on the spot (in Welsh, of course), you must allow entry and give the group food and ale. The horse may well misbehave and chase people around the house, while Punch and Judy will join in with the general chaos, with Judy also perhaps putting out the fire and sweeping the floor. In a very watchable video2 on the Mari Lwyd, Gwilym Morus-Baird suggests that the sweeping was thought to drive out bad spirits.

All quite fascinating: enough for the BBC to make a short film some time ago which you can see on Youtube3, although it will probably seem stilted to present-day viewers.

No record of the Mari Lwyd custom exists before about 1800, which seems odd considering how very ancient it feels. A number of writers have attempted, perhaps because of the late date, to show that Mari Lwyd means “Holy Mary”, but there are many other possible translations, including “Grey Mare”. There are also very localised names, including Aderyn Pig Lwyd or “Bird with the Grey Beak”. Ronald Hutton4 notes similar customs in Ireland and the Isle of Man and also points out that one function may well have been for poorer people to raise money or at least obtain food and drink during the cold of midwinter, while Violet Alford5 believed that the history of this and similar customs may derive from the Germanic Earth Goddess herself; during the early Middle Ages in some parts of the Low Countries and Germany people rode a “ship on wheels” around the country, dancing and celebrating as they went and this was believed to derive from the Nerthus ritual described by Tacitus and given in more detail below.

“Holy Mary” as a translation of Mari Lwyd seems the least likely and surely, if I wanted to celebrate the Virgin Mary in South Wales around midwinter I could think of better ways to do it than by carrying a horse’s skull around on a stick! Any number of similar traditions all over Britain point in an entirely different direction and there are hobby horses galore; in Kent, the practice of “hoodening” involves a hobby horse on a pole held by someone under a sheet, also performed around Christmas. Closer to Wales is the “Old Hob” celebration in Cheshire and Lancashire. Also worth mentioning in this context is the well-known Abbots Bromley Horn Dance, which features not only the reindeer antlers (which are heavy; I was once lucky enough to try on a set but unfortunately have no photo to prove it!) but also a hobby horse, among other characters.

There are also well-known Hobby Horse dances that take place around May Day at Minehead in Somerset and Padstow in Cornwall and on attending Padstow one year I managed to get right to the front of the crush, where an old woman warned me: “Don’t ee let ‘im get you under ‘is skirt, dear!”, referring to the “skirt” of black fabric hiding the operator. I saw any number of young women quite happily allow themselves to be pulled under ‘is skirt! It seems undeniable that this festivity, at least, is almost entirely about fertility, underlined by locals collecting green branches to decorate the town and the erection of a large maypole.

Herbert W Kille6 relates that at one time it was considered at Padstow that a woman touched by the ‘Oss was lucky, noting that this was understood to relate to child-bearing. He also quotes from an account written in 1881: “This hobby-horse was, after it had been taken around the town, submerged in the sea. The old people said it was once believed that this ceremony preserved the cattle of the inhabitants from disease and death.” It’s interesting to remember in this context that taking sacred images for a dip in the sea or a lake is still done. For example, at Saintes-Marie-de-la-Mer in southern France, every 24th May, the statue of St Sara is lifted from her crypt in the town’s church and taken down to the ocean, accompanied by men on white horses and crowds of onlookers, all of whom splash into the sea with their saint. Or Goddess? Further north, Tacitus tells us of a ceremonial wagon procession that took place in 1st century CE Germany; the Goddess Nerthus was taken around to great celebration, all iron objects, including weapons, having been locked away. Eventually the goddess was ritually washed in Her lake and returned to Her temple.7

Padstow Hobby Horse8

Returning to Morus-Baird’s video and taking all the research into account it seems impossible not to agree that the Mari Lwyd and other horse celebrations are about fertility; as mentioned in the video the women of the house are the real targets of the Mari Lwyd’s attention and certainly the Padstow ‘Oss is very interested too! But it is also about death, the other side of the coin to fertility, of course, supported by ideas mentioned by Ellen Ettlinger9, that at one time the ceremonies were perhaps performed at Samhain, also that in some places the celebration was called Marw Lwyd, which could mean “Grey Death”, perhaps of the old year as Samhain at one time marked the coming of the new. But “grey” also reminds me of pre-Christian ideas of the underworld, which was often seen as a dull, grey place, devoid of interest.

Morus-Baird also mentions that a relationship between horses and fertility is common in Welsh folk tradition; after a marriage ceremony bride and groom would get on a horse and ride home but if the groom touched the reins or tried to steer that was bad luck and the marriage would be childless. Was this about trusting the nature of the horse or of the new wife? Interestingly, in North Wales, horse skulls would sometimes be placed outside the homes of women known to be having an affair.10

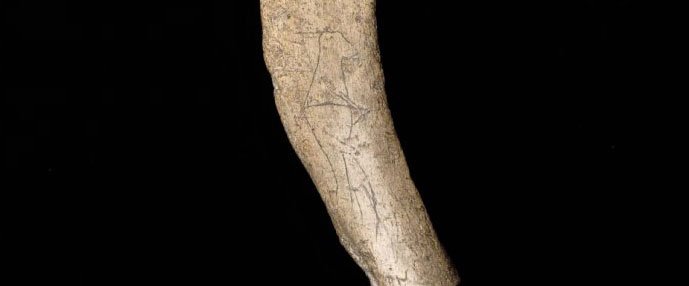

How far back in time do these ideas go? Perhaps the oldest indication in Britain was found in the Pinhole Cave at Creswell Crags in Derbyshire: an engraving on a woolly rhinoceros rib bone, which dates back to the Upper Palaeolithic (anywhere between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago) of a man (very obviously, if you look closely!) apparently wearing a horse mask and dancing. I’ve edited the photo below to show the carving as clearly as possible.

Pinhole Cave Man11

More recent is the story of Rhiannon – whose name derives from an earlier “Rigantona” which means “Great Queen”; herself, according to Hemming12 a regional variant of Epona. Very briefly, part of her story appears in the First Branch of the Mabinogi where she appears to Pwyll, prince of Dyfed, as a beautiful woman riding a shining white horse, and although she seems to be riding slowly none of the horsemen Pwyll sends after her can catch up, and only when he follows her himself and asks her to stop does she allow him to approach, then explaining that she wishes to marry him, to which Pwyll agrees gladly. In time they have a son, but he is abducted immediately after birth. Rhiannon’s terrified maids kill a puppy and smear its blood onto her face to avoid blame for themselves and Rhiannon is accused of infanticide. There is little she can do to defend herself and so offers herself up for punishment, which involved having to sit by the castle gate to tell her story to travellers, whom she must also offer to carry on her back, although few accept. Hemming notes that some have viewed Rhiannon’s adoption of the behaviour of a horse as because she is as much mare as woman, or in some cases that in some (unknown) primitive version of the story she has birthed a colt as well as, or instead of, a boy.

Rhiannon, clearly a horse Goddess, perhaps embodies the spirit of the land. This idea of a mare as deity of the land, of sovereignty and fertility, is found in many Indo-European cultures, all of which spring from the same root as that of the Celtic people: the belief can be found in Vedic texts some 3,500 years old: an ancient ritual called Asvamedha identified the horse with the universe and the creator and was instrumental in the acquisition of sovereignty and the well-being of the people.

We’ve come a long way from South Wales, tracing back, perhaps, some of the path our Indo-European speaking ancestors took across Europe, bringing with them both beliefs and rituals involving horses. But I’ve barely scratched the surface here and look forward to expanding this article further.

Geraldine Charles

Yule 2023

- Used with permission

- Celtic Source (24 January 2020) Mari Lwyd – The Welsh Sources and Meaning [Video] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YU5pk-Hc758

- BBC Cymru (15 February 2011) Tradition of the Mari Lwyd [Video] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G_xFo6Hifzk

- Hutton, R. (1997) The stations of the sun: A history of the ritual year in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Alford, Violet. “Some Hobby Horses of Great Britain.” Journal of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, vol. 3, no. 4, 1939, pp. 221–40. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4521156(accessed 8 Dec. 2023)

- Kille, H.W. (no date) West Country Hobby-Horses and Cognate Customs, The Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society. Available at: https://sanhs.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/14-H-W-Kille.pdf (accessed: 27 November 2023).

- Tacitus Germania (no date) Tacitus’ Germania. Available at: https://facultystaff.richmond.edu/~wstevens/history331texts/barbarians.html (accessed: 14 December 2023).

- Photo: Bryan Ledgard – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%27Oss,_%27Oss,_Wee_%27Oss!_%28496597655%29.jpg

- Ettlinger, Ellen. “74. The Occasion and Purpose of the ‘Mari Lwyd’ Ceremony.” Man, vol. 44, 1944, pp. 89–93. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2791738 (accessed 8 Dec. 2023)

- Celtic Source (24 January 2020) Mari Lwyd – The Welsh Sources and Meaning [Video] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YU5pk-Hc758

- Pinhole Cave Man from the British Museum via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pinhole_Cave_Man-1.jpg (edited)

- Hemming, Jessica. “Reflections on Rhiannon and the Horse Episodes in ‘Pwyll.’” Western Folklore, vol. 57, no. 1, 1998, pp. 19–40. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1500247 (accessed 8 Dec. 2023)